"To understand the rise and fall of empires, we must follow the paths traveled by grain."

-Scott Reynolds Nelson

Welcome to the first edition of my interview series. In these intimate conversations (I like the name “Wood-fired Side Chats”--let me know what you think), I will be listening to what I care about most: the stories behind our recipes.

I have a roster of the world’s most committed, ingenious, and obsessed bakers, farmers, historians, millers, and writers who will tell us their tales. Whether it’s a seventh generation farmer in India changing the grain landscape in the world’s largest democracy, one of New York’s most creative and finest pastry chefs, or a baker who single handedly mapped all the sourdough starters in the Czech Republic, these are people whose Visions inspire me beyond description. And I want to share their gifts with you.

I’m honored to kick things off with the author of one of my favorite books. Scott Reynolds Nelson’s Oceans of Grain: How American Wheat Remade the World is a tour-de-force which positions wheat as the most important crop–and weapon–in ancient and modern history. The Financial Times called his book, “An incredibly timely global history journey from the Ukrainian steppe to the American prairie to show how grain built and toppled the world's largest empires.”

Join us on a fascinating rollick through the wheat fields of history and how grain made, and continues to make, our world. Along the way we’ll bump into Napoleon, Stalin, Lincoln, Trotsky, and Russia’s War on Ukraine.

I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Graison Gill: Scott, thank you for joining me. The first thing I'd like to ask is what's your first bread memory?

Scott Reynolds Nelson: It was the fourth grade, or fifth grade, outside elementary school and there were women who made these amazing rolls for breakfast. And our house was about half a block away from the school. At about six in the morning,we would wake up and smell the amazing smell of these rolls. At the elementary school, most of the kids were on free and reduced lunches–so that's why we’d smell the rolls first thing in the morning and again at lunch.

GG: So it was comforting–something warm and hot and starchy and filling?

SRN: Yeah, it definitely was. Because when you smelled the rolls you knew they were there again for lunch; those lunch foods would always disappoint but the rolls would be excellent and so you’d try to get the Lunch Lady to give you another roll. But unless you were really good at it you were not going to get another one.

GG: Yeah, or if you just showed her enough attention, you could get some empathy rolls.

SRN: Exactly, exactly.

GG: That’s great, thank you for sharing. Now if you could, please give me a simple introduction to your book.

SRN: Ok. But let me tell this in a little different way. Since we started with food, one of the earliest memories that I have of my grandmother is her telling me about her grandparents…So I was kind of raised by my grandmother and my grandmother was raised by her grandparents. They left Sweden in 1878 when things were very bad, the bottom of a depression, and my great grandfather remembers two things: hating his stepfather and being starving. One day my great grandfather found some apples and he put them up a tree so that he could get them later. His stepfather saw him put the apples there and he went over to the tree and he peed on him. This was the last straw for my 16 year old great grandfather and he did everything he could to escape from Sweden. He was so hungry and so unhappy. He left and that was because of food. So this memory of hunger was something familiar to him and he passed it on to my grandmother. My grandmother told me that the Depression of 1873 was world shaping. And so for me, that was an important part of how I thought about my relationship to my family; ever since, I’ve tried to understand the immensity of that Depression.

So, in 1985 or so 86, I'm writing my senior thesis and it's about the shift from iron to steel and the panic of 1873. And as I was reading all of these documents by steel manufacturers and railroads, they all said this was about wheat; that to understand this financial panic you had to understand wheat. That puzzled me, because American historians say that the Panic of 1873 had everything to do with a particular financial person who failed in Philadelphia and that was the cause of the panic. The German version of the Panic of 1873 is a housing bubble, the Russian version of the Panic is a crisis that starts in Ukraine and so I was struck by how each nation had its own explanation of how the Panic/Depression of 1873 started. So I was persuaded by the people at the time who said that the Panic had everything to do with wheat and it became a fascination. It was not something I could write a book about in 1986 when I was 20 years old. I wrote a bunch of other books, but in my mind the white whale was telling this story about wheat, and how a world market for wheat was at the center of this financial panic.

I realized that we’re all bound together by food, not by oil, not by energy, but by food. In one book I found a person named Parvus, my man crush, who explained to me, finally, what was going on. In a piece that he wrote in the 1860s, he explained how a financial panic was developing and his explanation was that Ukraine had been replaced by the United States as the world’s bread basket. So, that's how I found out that Ukraine was at the center of the Panic of 1873…

GG: Speaking of Ukraine…in your opinion, do you feel like the rise of food prices was justified with the invasion of Ukraine in 2022? And then if so or if not, why didn’t we see prices rise during the Crimean invasion in 2014 or during the Chernobyl disaster in 1986?

"The war in Ukraine is a war for the wheat and corn that has fed the world, back to the Stone Age."

-Scott Reynolds Nelson

SRN: That's a great question. Let's just zoom back a little: in the 1790s the world's at war. Napoleon is invading, he's moving across Europe, but the one place to get wheat is the Black Sea, in Ukraine. It's a safe, neutral place because the British and French are not fighting with each other there. And so, wheat from Ukraine fed Europe during Napoleon's Wars. Because demand for wheat increased during the war, bread prices also went up during the war. But Ukraine comes to the rescue and it develops rapidly: it feeds Europe and does so from the 1790s all the way to the 1860s. So if you get a bun or a or a local bread in London, Liverpool, or Amsterdam, it came very likely from Ukraine.

GG: This grain is all milled and distributed and baked locally, but sourced, grown, and transported from Ukraine?

SRN: Exactly. It's milled locally in these big cities but it comes from Ukraine. (I promise, I'll get to Crimea). So then the United States emerges in the 1860s, after the Civil War is over, it starts to feed the world, it by far outstrips Russia in terms of its power for a lot of complicated reasons: industrialization, urbanization, etc. But fundamentally Russia, because of its possession of Ukraine, had been the world's provisioner of food for a long, long time. This all changed with U.S. hegemony after the Civil War: the U.S. replaces Russia/Ukraine as the world’s breadbasket. From then on, from around the Russian Revolution all the way up until the 1980s and 90s, Russia was only feeding other parts of the Soviet system.

Some historians have argued that the key to understanding why the Soviet Union fell apart is this: the great grain invasion. What happened is that the Soviet Union began buying its food from the United States, and because of this it went into a fiscal crisis, then a military crisis, then another military crisis, and then the Soviet system was over. Russia was trying to recover in the mid 1990s by exporting food: throughout this time, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ukraine is building back its capacity to export wheat just in the way that it had from 1793 until 1917. And that capacity didn't really get to crucial levels until 2005-2007. This is why the Crimean invasion in 2014 doesn't see any grain stop flowing out of Ukraine. All the while, by the early part of the 21st century, Russia had become the world’s leading wheat exporter once again. The key is that most Russian grain bound for export has to go through Ukraine.

It's a really long answer to a very short question. But that's why we don't see these other conflicts in/around Ukraine mattering as much. However, by the 2010s, the world is dependent on Russian grain and Ukrainian grain. And so that's when we see the Arab Spring: it takes place when Russia blocks all grain exports in 2012. This led to a huge price spike across the Middle East, a place where in most countries grain is subsidized and wheat is crucial for keeping cities alive. The countries which can no longer subsidize cheap grain are led into chaos: Tunisia, Egypt, Libya…

GG: Like Ancient Rome?

SRN: Like Ancient Rome.

GG: Speaking of the old days, let’s talk about Ancient Greece. Scott, can you please tell us about “Persephone’s Secret”?

SRN: In the ancient world, people knew how to transport grain in a way that became lost during the Middle Ages; specifically, they lost the knowledge of how to store grain for long periods of time. And one of the things I talk about in the book is the Greek myth of Demeter and Persephone, her daughter. Persephone is kidnapped by Hades, and Demeter demands her release. He refuses, they bargain: Hades says she can come up nine months out of the year. Those other three months, during the winter, she stays down here, he says. And so one of the things that I show is that this is not a story about the planting of grains: it’s a story of storing grain. The ancient Greek world knew how to store grain underground. This is a problem for Alexander the Great because as he tried to take over this part of Europe, he discovered that, if grain is stored underground, you can't find out where it is.

Well, in the Dark Ages, after the Roman Empire collapsed, farmers lost the knowledge of how to store grain for more than a year or two at most. This makes feeding people–and nations–incredibly tricky. So Napoleon, after conquering Italy, sends a scientist named Chaptal to try to rediscover the secrets of Caesar as he calls it: in other words, how did the ancients store grain for long periods of time? And what does Chaptal do? He kind of reverse engineers the process. He finds a big enclosed, sealed vessel, the size of a large room. That’s when he says, Oh, I see what’s happening. The ancients were heating and drying the grain to get rid of all the air and this makes the grain go to sleep, like Persephone goes to sleep, once she goes into hell. And with this new knowledge, of storing grain in an anaerobic environment, Napoleon uses this to provision his troops as they're marching into Russia. That does not work especially well for him, but Persephone’s Secret goes out to the world because Chaptal publishes his results. Suddenly, the world rediscovers how to store grain, not for a year or two, but for 10 years, for 20 years, for a hundred years.

After this re-discovery, the grain elevator and silo become a new form of the bank: they are a storage container of the world’s most crucial food. By the 20th century, once further improvements were made to this storage process, you see an explosion of the productivity of wheat grown in Russia, Ukraine, and the U.S. This is why–if you travel through the mid-West or any other farming area–you see silos. And grain elevators. These are nothing but sealed chambers where grain can wait for the market. So these efficiencies of growing, storing, and transporting grain create a perfect storm where we can feed a growing world for cheaper. [There’s no coincidence that the population of the earth exploded right after the discovery of “Persephone’s Secret”: in 1800, the earth’s population was 1 billion. Now, it’s 8 billion. That’s a 700% increase in little over 200 years].

"The cheap wheat produced by the American Civil War helped bring the world to the brink of famine, world war, and international revolution."

—Scott Reynolds Nelson

GG: Something very fascinating, that I want more people to learn about, is the “coincidence” that slavery in the U.S. and serfdom in Russia ended within two years of each other. Can you please talk about how this happened?

SRN: Yeah. Wow, let's see. So we think of slavery and serfdom as different and they are different. But legally, a serf had or could have some partial ownership of the land. A slave in the US had no ownership of the land. But Catherine the Great, in the 1790s, “reforms” serfdom to become more like slavery: serfs can be bought and sold as children in Russia. And so something more like chattel slavery existed in Russia after the 1790s.

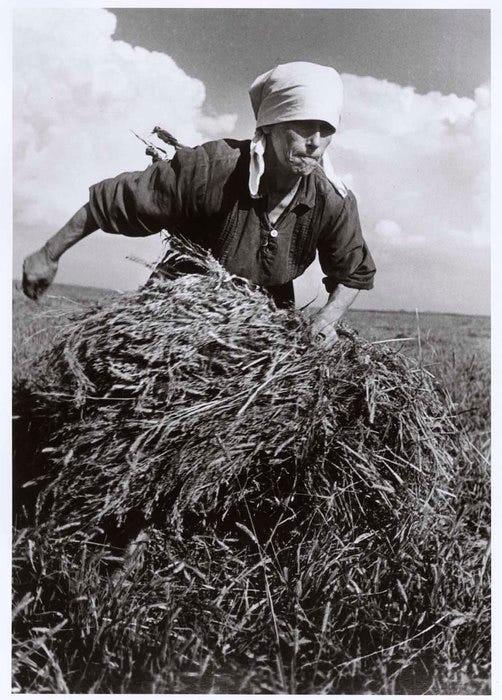

So we have two parallel systems. Except when it comes to the crop being grown. You see, the thing about wheat is that it doesn't require the kind of intense labor that cotton does. Cotton is something that has to be constantly attended to: it has to be grown and suckered and trimmed and weeded almost all year long. So in the US, people had to work year-round to produce and harvest cotton. With wheat though, if you’re basically an okay farmer and know something about the land and planet, you have about a month of intense work for the planting and about a month of intense work.

GG: But then it’s pretty hands off after that, except for the planting and the harvest.

SRN: Yes, so there’s relatively little you do in the meantime. Therefore, slavery doesn’t work in an environment where wheat is grown. Also, cotton has to have 200 frost free days and so it tends to be associated with the South, where it’s very warm. On the other hand wheat needs relative cold. And so, wheat tends to grow further North and cotton further South. And that's really the difference, you know, if you're going to talk about a line between freedom and slavery in the U.S. Therefore, the most successful wheat farmers are not people who have a lot of slaves, but farmers who hire help for a month to perform the harvest for them.

So you start to see two kinds of worlds emerge both in Russia (Ukraine is part of Russia at this time) and in the United States. It's a such a long story and I don't want to get too much into the details, but basically these two social systems of serfdom and slavery collapse at almost exactly the same time…In the 1850s Russia is trying to expand; it tries to defeat the Ottoman Empire and therefore gain full access to the Black Sea so it can freely ship Ukrainian grain around the world. This attempt leads Britain and others to fight against Russia in the Crimean War, where the Russians are defeated. After its loss, Russia spirals into a financial crisis. The Czar’s officials realize that the only way they can buy themselves out of the crisis is to end serfdom: they devise a method in which serfs may purchase their freedom by paying that State back over time. This buffers the government’s coffers and gives former serfs not only freedom, but in some cases, their own land.

In the United States, a much more cataclysmic conflict between people who are connected to the land unfolds. Some people, concentrated in the North, are convinced that free labor is the best way to grow crops and they will fight like hell to prove it. In the 1850s, they made sure that Kansas was a free territory because that land is so valuable for grain. So really, the Civil War began in Kansas over whether Kansas would be a free or slave state: this is what Lincoln wants to defend. He doesn't, he says, care about slavery in Georgia. He doesn't care about slavery in North Carolina, but he doesn't want slavery in Kansas. And he doesn't want slavery in the corridor to California and lots and lots of other people agree with him and are willing to die for that. We're used to thinking of the United States as fighting wars that are primarily about principles, and principles are involved, certainly in the Civil War. But it’s also about land and soil and what’s the United States going to do: feed the world with wheat or clothe it cotton?

Unfortunately, for us, our conflict ends differently than the Crimean War: in that conflict, serfs get land. The way our conflict ends, the former slaves did not get land. And so many of the problems of the United States today have to do with the fact that we did not give land or sell land or mortgage land to the formerly enslaved.

GG: So is it fair to say that serfdom ended because it wasn’t profitable? And our Civil War was just as much about slavery as it was about economics and agriculture?

SRN: Mostly, yes, that’s correct.

GG: One thing that I feel, once again, needs a lot more attention is the holocaust in Ukraine in the early 1930s. Historically, I see an irony that the world’s richest agricultural lands was the setting for one of the world's worst famines. So I'd like you to talk about the Holodomor (Ukrainian for: “Death by Hunger”). Please tell us what happened.

SRN: Absolutely. So one way of thinking about this is how Stalin saw it. When he became premiere, everything that he had to do had to be approved by the grain merchants. And by large landowners, who were called the Kulaks. There's thousands of them, tens of thousands of them, including Trotsky’s father (who was a wheat farmer and Kulak from southern Ukraine). Most of the Kulaks were not Jews like Trotsky’s father, but instead ethnically Ukrainian or Cossack. But they were very powerful and very important because they controlled the grain: therefore, they controlled the country.

The Russian Revolution began with a famine in St. Petersburg and Moscow. So feeding St. Petersburg and Moscow is crucial to the Soviets and Stalin learns from those early years that having a market which dictates the price of wheat is a terrible thing because it can lead to speculation and price spikes. So in the early 1930s he created a system that basically says all farmers have to harvest all of their grain. And not save any for replanting the next season, which is crazy. Absolutely crazy. And then these same farmers have to request seed to plant it again. This is all an attempt to break the Kulacks, really it’s to make them pay for their own seed as opposed to saving it themselves: allowing the government to control the seed, as opposed to the farmers, shifts the balance of power firmly into Stalin’s hands.

Needless to say, this is just an absolutely stupid way of organizing the distribution of grain. And it becomes, in a short time, an enforced famine [which not just affected Ukraine, but the entire Soviet Union]. Whether Stalin actually plans to kill people in large numbers is an open question. His real goal is to break the large scale farmers, the Kulaks, who are growing grain on hundreds of acres, and in doing so creates this crazy artificial system of pulling wheat off the farm and then sending it back to be replanted. Lots of the wheat spoils during this transportation and a lot of the wheat doesn't get delivered. And so by the early 1930s, due to this tactic, Ukraine and its traditional agricultural system of large wheat farms run by Kulaks and peasants was basically starved into submission. It's a genocide; people ate shoes, people ate the corpses of other people. I mean, just horrifying. Millions died, tens of millions suffered. And it was all an attempt to control the golden egg, the precious golden egg of Russia: Ukrainian wheat.

GG: The estimates are between four to seven million killed. …Some of my ancestors barely got out in time. Gareth Jones, the famous Welsh journalist, went there to report on the genocide. And his work was silenced by The New York Times.

SRN: It’s horrifying and it really helps us understand the kind of sense about people in Ukraine and their relationship to Russia today: the Holodomor is a really important factor in shaping this current war as a colonial process that the Russians are engaged in.

"The choice is between freedom and fear."

—President Zelensky

GG: Scott, can you please talk about the varieties of wheat grown during this time both in the US and Russia/Ukraine?

SRN: Sure. So I think it's Mencius, the Chinese philosopher of the Warring States period, who says we remember the names of kings, but we don't remember the most important people: those men and women who figured out how to grow more seeds and how to select certain seeds and grow them again. And in short, we couldn't have colonized the United States without the different land races varieties of Ukrainian and Russian grain that were brought here, frankly smuggled here, in the 19th century.

You see, it was farmers [in Ukraine and Russian] who grew these varieties over hundreds and thousands of years to produce all these different wheats [called landrace or heirloom]. The great thing about wheat is if you have just a few thousand seeds, after just three or four harvests you can grow that stock out and cover hundreds of acres with that grain. And so, this seed smuggling allows people to settle in places of the United States–Kansas, North Dakota–that previously wouldn't have been able to support wheat agriculture because the varieties available weren’t suited for that climate. But when farmers–and smugglers–arrived in America with wheat varieties from Ukraine and Russia in the early 19th century, American wheat agriculture exploded due to these varieties. In other words, nothing else could grow in these colder climates except the seeds from Ukraine and Russia: Red Fife, Turkey Red, Halychanka, and the like.

"Empires survive only as long as they control the sources of food needed to feed soldiers and citizens."

—Scott Reynolds Nelson

GG: I was once told ten years ago, by one of the country’s best wheat breeders, that something like 75% of the germplasm of grain grown in North America comes from Ukrainian and Russian seeds. So, like you’ve said, if we didn’t have this DNA the U.S. would not be what it is, not just now, but 150 years ago as well too.

SRN: Right, and the Land Grant system in the U.S. made all this possible. They began to ask the questions: how do we get more out of the land, how do we feed people cheaply, how do we feed the rest of the world cheaply? And that's really been the mission of the United States from its founding all the way to today. It’s what made it a world power and again, it would be possible with these Ukrainian wheat.

GG: Okay Scott, I can talk to you for another five hours but I want to let you go. Thank you so much for being so generous with your time. I really appreciate it.

SRN: Thanks so much. Thanks so much for reading my book so carefully, this was really amazing.

hello from eastern Ukraine, this interview was fascinating

Highly, highly informative. I'd never heard about the north - south division of wheat vs cotton and slaves vs twice a year labor. Not did I know 75% of wheat germplasm comes from the Ukraine and allowed the US to become a grain empire. Thank you for this highly informative interview!