“O beautiful for spacious skies,

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountain majesties

Above the fruited plain!

America! America!”

I couldn’t stop staring at her boobs. Because she came over three times to refill my sweet tea and each time she bent over and asked if I needed something, maybe some more ranch for those hot wings? they were there and so were my eyes. I was 23, maybe 22, immature enough to be looking and mature enough to be ashamed. It was my first time in a breastaurant and my nerves and the loudass Nickelback and the FD&C Red 40 from the chicken wings were working me without mercy. I was a long way from the lentils and jazz and unfiltered Camels of my apartment in New Orleans.

Then Toby Keith came on and the guy I was waiting for came in. He was taller than I thought: Tom Selleck mustache, Dockers chinos, an untucked shirt as wrinkled as the corners of his eyes. He didn’t know what I looked like but he came right over to my booth: either because I was the only one not lip synching to “As Good As I Once Was” or because no one else would wear a tweed newsboy hat and gingham button down in a place like this.

I’d spent a few years trying to take this guy out. But my overtures were always rebuked. And then one time, for some reason, he finally said yes. And when he did I said, “I’ll take you to any restaurant you want.”

“Do y’all want some more wings to go with them cheeseburgers you got comin’?” The fabric of her striped shirt stopped where the cleavage began. And a whistle–bright as a nickel on the bottom of a deep fountain–was resting there. She was dressed as a referee, I was dressed like an extra in a highschool production of Les Mis, and my date said “Yeah, we’ll take a dozen more.”

I was sitting across from one of Louisiana State University’s (LSU) most important agricultural professors. And like I said, I’d known the guy for years. But only in the way the Internet allows you to know someone: I knew that he studied the sex life of wheat and corn and other cereal crops, that he knew the Latin names of weevils and beetles and aphids. His path to becoming a PhD of Triticum aestivum was as tidy as a field of wheat.

While he was learning all this, I was rollerblading in Jnco jeans and smoking weed from cored apples. My path to being a baker was, well, a bit zig zagged. Yet here we were, to talk about what he knew and what I wanted to understand: how can I use Louisiana-grown wheat in my bakery?

So when he suggested this lunch in Baton Rouge, close to LSU’s campus, I drove two hours in traffic there and three hours back because I thought it would get me closer to my obsession for local wheat.

“Alright boys, so another round of wings. Want some wet wipes in the meantime?” She smirked, I blushed, and the Wheat Doctor began to speak.

“So you want to bake with wheat grown in Louisiana?”

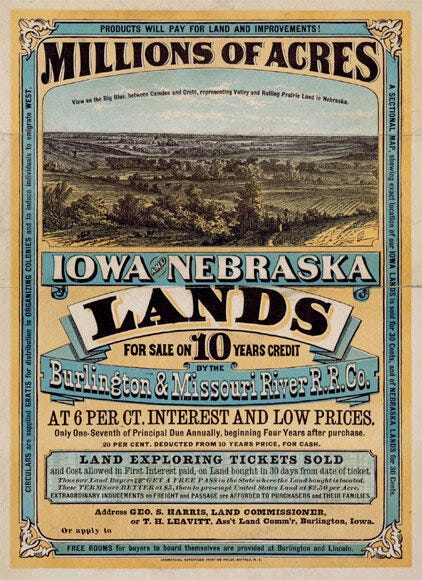

The summer before the Emancipation Proclamation, President Lincoln signed two acts which had tremendous consequences for American agriculture. The first was the Homestead Act, which was designed to incentivize slavery-free westward expansion by subsidizing the cost of real estate for new settlers. And its cousin, the Morrill Act, was designed to teach these new land-owning citizens how to become more efficient and productive farmers.

At this time in the U.S.'s history, most Native Americans who hadn’t been killed by European germs or violence were concentrated on reservations. This left wide swaths of the Heartland vacant; Washington’s idea was to populate these expropriated lands–Nebraska, South Dakota, Iowa, Indiana–with smallholders. Under the Homestead Act, 160 acres of land were sold for next to nothing to thousands of farmers who swarmed aboard the newly built railroads to till the American Dream.

The wide planes and rich soils of these places, along with their warm summers and cold winters, were perfect for one crop. Wheat.

With passage of the Homestead Act, the Feds got what they needed–a new tax base, a constellation of settlements across the bulging frontier, and yeoman farmers incentivized by cheap land to be responsible citizens. This agrarian republic, built on the solid foundation of land-owning and self-reliant small farmers, was Thomas Jefferson’s dream for America. With its small plots, family farms, cheap transportation on the railroad to market, and technological innovations such as the reaper and combine, the Homestead Act underwrote Manifest Destiny and taught America how to feed itself.

But the federal government did not just give small parcels to farmers. Under the Morrill Act, also passed in 1862, over 10 million acres of expropriated land were gifted to the states by the federal government in the so called “Land Grant” system. But there was a catch: to receive these land grants the states had to establish public universities and colleges “to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts…in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.” The Feds were wise enough to anticipate that handing out land to smallholders at firesale rates was pointless: they understood that these new farmers needed an infrastructure to teach them how to become even more efficient American farmers. State and college universities, all of which still stand today (LSU, University of California, Texas A & M, Oklahoma State, University of Iowa, and Clemson to name a few), were created by the Morrill Act.

In the decades after their founding, the Land Grants became the pinnacle of American ingenuity. A sort of crowd-sourced Silicon Valley, they were a fulcrum of technology, agriculture, innovation, engineering, research, and seed breeding. By harnessing public resources (land, revenue, bureaucracy) and leavening them into public innovation (reliable public seeds, free information, accessible research), the Land Grants built the foundation for the America we recognize today. All this was achieved by breeding new seed varieties, by researching new growing techniques, by adapting varietals to different climates, by innovating new methods of irrigation, and by listening to the local, geographically-specific needs of farmers. And all of it was done in the public’s interest, for free (or minimal expense), by educating the sons of farmers to become better farmers than their fathers.

The stereotype of Carnegie, Morgan, Rockellefer, and other Barons forcing progress and innovation on post-Civil War America is true. But what really changed America–and its role in the world–was the food it grew. Rising yields, massive acreage under plow, new and modern varietals, efficient transportation, and an unrelenting desire to do better and make more underwrote the tremendous success of American agriculture, and therefore America, during the mid to late 19th century. None of this would have been possible without the Homestead and Morrill Acts. (It’s important to mention that, during the Civil War, the South starved while the Union was not only feeding itself and the liberated Confederate States–it was also exporting huge amounts of wheat to Europe because of the success of these Acts. In fact, by the end of that war, wheat grown in California was renowned around the world, usurping the reputation of Richmond, Virginia for making the finest flour).

It was then, when America began to feed the world, that it became a world power. And it was the Land Grant schools, coupled with the Homestead Act, that changed what before them was an American experiment into the American experience. Not by proving that this country could work, but by proving that it did.

This is why I was at lunch that day.

One guy told me to fuck off. A lot of them hung up on me. Some laughed. But mostly it was unreturned phone calls, unanswered emails, and kind secretaries who swore they’d give the professor my name and number first thing on Monday morning, honey.

I was too young, and too single, to recognize that this was rejection. It was 2009, a few years before the breastaurant, and I was reaching out to every Land Grant school in the South. While my friends in New Orleans were out being kids–sewing Mardi Gras costumes, playing in bands, riding freight cars, swapping spit–I was spending my free time in an Internet Café copying down the numbers of all the wheat breeders at Southern Land Grants into my Moleskine. Then I’d go home, try to find privacy in the 800 square apartment I shared with four people, pick a name, dial the number, and give the professors my pitch.

“Hi, I’m Graison Gill and I’m a baker in New Orleans. I’m interested in wheat that is bred for flavor, not yield. I have a small flour mill and I’d like to learn more about the varieties you’re growing, as well as any farmers who are growing them. Do you have a few minutes to talk?” If I were lucky enough to get someone on the phone, I’d be even luckier if I made it past a few syllables. The dial tone–its hollowing, consistent timbre–became as familiar as my heartbeat.

Despite the rejection, I was undaunted because I was obsessed with finding local wheat. Ever since I began to explore flour and wheat as ingredients which have flavor–not just generic products sold in 50 lbs bags–I had a dream to source regionally and locally grown wheat to use in my bakery. I had a mad vision that the food system could be remade in the image of those who fed us–farmers, families, millers, bakers, breeders–not the brands, companies, and corporations who crippled it. But my hubris was that I thought persistence, coupled with my righteousness, would be contagious. After two months of those unrequited emails and phone calls, I realized I was obsessed and wrong.

But then I had an idea. What if I gave these Land Grant professors historical proof that this used to work?

That’s when I began to go to Tulane University (not a land grant) to read archival documents. It was there that I found out the French, when they arrived in New Orleans, immediately planted wheat in Bayou St. John. I also found out that a stone mill, run by slaves, operated where the Audubon Aquarium now stands. And a few decades after the city’s founding, when Europeans realized New Orleans was too humid for wheat, a thriving trade was established when grain grown in the Upper Mississippi River Basin was shipped to the city. This wheat not only fed New Orleans, but was shipped to Mexico, Cuba, and farther afield. Last, but not least, I found out that certain soft wheats grew well north of Baton Rogue because Land Grants had researched the seed and made it available to local farmers.

Eureka.

South Louisiana had a local and regional grain chain. It just needed to be put back together.

“What do you want, Graison?” I couldn’t get the smell of blooming onions out of my nostrils and the dye from the chicken wings was staining my fingers.

“Well, doctor, I’d like to start using Louisiana-grown grain in my bakery. And I’d like you and me to work with regional Land Grants to research the old varieties that used to be grown in the Basin.” He looked at me with pity, like an adult about to tell a 3rd grader that Santa doesn’t exist (thankfully I’m half Jewish so I had a head start on him).

I interrupted to prolong the embarrassment. “I know that right now Louisiana grows 60 million dollars worth of wheat per year. I know it all goes to animal feed; but what if, instead of growing this cheap wheat that people don’t eat, we find out what varietals can do well down here? If we did this, the farmer could earn more money by selling the grain on the direct market, local bakers and consumers would get a healthier wheat, and we could improve the quality of the soil by growing more ecological seeds? I mean, isn’t this what the Land Grant is supposed to do–serve its stakeholders by providing research and quality seeds?”Now, his look turned into a glare, as if a half-Jewish 3rd grader just told him that Santa doesn’t exist.

Over the last of the wings and half-baked undergrads and pints of Arnold Palmers, my naive hope about working with the Land Grants wasn’t just deflated. I was eviscerated.

The Wheat Doctor told me a lot and was very generous with his time. And I’m still unsure if my expectations, or his explanations, are what hurt more. Regardless, that lunch was a crash course in American farm policy: the disconnect between eaters and farmers, the abysmal state of grain in America, and how our public institutions have become private boardrooms.

What’s happened is that, over the past 80 years, the Land Grant system has become a research firm for private seed companies. Instead of responding to local farmers, the universities began to react to market factors: their prerogative slowly shifted from serving diverse small farms to serving larger and then huger corporate farms. Where they once researched and developed grain varietals which were well suited to local climates and the small to mid scale farms of their constituents, Land Grants shifted their research to high yielding and disease resistance varietals for these massive farms. This was because its new constituents, Big Ag, weren't interested in crop rotation, diversified farming, or flavor. They wanted, and still want, profit. In wheat, this translates to yield: the more you harvest, the more you make.

So it was in this way that food and farming in America after World War 2 became a business. And because of this, so did our Land Grants.

This change inaugurated two major shifts. The first was that when the constituents of the Land Grants changed from farmer to corporate firm, the cultivation of wheat became more concentrated. Where once wheat was grown throughout the country as part of diversified farms, it was now relegated to massive monoculture enterprises in places with proven high yields ( Midwest). In turn, the smaller pockets of regional wheat cultivation (Northeast, South, California) were withered and transitioned into cash cropping. A glaring consequence of this shift was the imbalance it created in biodiversity and soil health. But the most glaring consequence of this shift was how it destabilized our diets: when we stopped eating locally and regionally, our country began getting heart disease, diabetes, and generally sicker at an alarming rate.

The second shift is that normal people–like me, like you–became disenfranchised by the Land Grants. These days, if an artisan baker or miller or small farmer goes to the Land Grant for wheat seeds, it’s like someone going to their local library and asking for books by Anaïs Nin and James Baldwin. “Sorry,” the librarian says, “We only stock books on computer engineering, blockchain, and digital marketing because that’s what Amazon, Tesla, and Google want their employees to read. It’s a new policy.” Then the citizen says, “I didn’t get that memo. I pay my taxes, which fund this library…Can I see a copy of the changed policy?” “Well,” the librarian says, “We never officially changed the policy. It’s just different. There’s a little free library out back, you’re welcome to rummage through there.”

This is how it works: a Land Grant’s legal and historical focus is to research, and then release to the public, quality seeds at an affordable price. But what these private seed companies do is take this thoroughly researched information from the Land Grants and then mine the genetic data of these public seeds. They then slightly tweak a gene here, throw an extra disease-resistant diploid there, and voila they have a “new” seed which they promptly patent. Promising that they’re more efficient and higher-yielding than the original public varietal, these companies then sell their private seeds back to the very people who paid for their research and creation in the first place: farmers. And who eats that flour? Every one of us.

“The eternal raison d'etre of America is in its being the "sweet land of liberty". Should a land so dreamed into existence, so degenerate through material prosperity as to become what its European critics, with too much justice, have scornfully renamed it the "Land of the Dollar" - such a development will be one of the sorriest conclusions of history, and the most colossal disillusionment that has ever happened to mankind.”

― Frank Norris

The Wheat Doctor told me none of this of course. He did say that his prerogative, as a public employee, was to serve the needs of his constituents. But his constituents are Big Ag–Monsanto, Sygenta, Cargill, Corteva, and their ilk. And they loiter in the shadows of this country like the Five Families of New York: they sanitize the narrative of their work (“Feeding a growing world! We help make food systems more resilient!”) and they plaster Land Grant schools with tax-write off donations by sponsoring buildings in their names. All the while, it’s our public money which is subsidizing their privatized profits.

“What you want to do, Graison, is a fine idea. It’s just too small. Bakers like you can only buy so much wheat–barely a drop in the bucket. I just don’t have the funds to research something which has no market share.” In plainspeak: Your dreams, no matter how plausible, aren’t possible. There isn’t enough money in them.

I felt small. Small as a grain of wheat in a field of an awful truth.

I had come to lunch hoping I could blow the whistle on the American food system and convince this guy to do something different. I wasn’t pretending to be a savior, just a hopeful and naive American who knew about the days when Land Grants and their constituents worked together in a civic spirit of progress and mutuality and affordable tuition to make food better and more plentiful. Best of all, most surprisingly of all, it was that the government made this successful. I had to beg forgiveness for my nostalgia.

Nothing in American agriculture changed that day. But someone changed that day.

Me.

In some fundamental, painful way, I became an adult that day (despite the boob staring). Because during that lunch all the previous rejections via phone and email were rolled into one: I was finally and firmly told to my face that my dream was impossible–wrong, silly, cute, dumb. I was told no.

So I decided on that day that I would always tell myself yes.

I became an adult when I refused to let my passions and dreams be regarded as childish. This was conviction, but really it was faith. There’s no fertilizer quite like it. And it’s what our country, I thought, was meant to stand for. I can still see that place, sometimes, even if I have to squint.

Happy Inauguration.

Absolutely loved reading this Graison - super interesting

That was a riveting and incredibly informative read. I’m ashamed to say I knew nothing about Land Grant schools before this piece. Well done.

Taking those seeds you planted of resilience and not letting go of what others consider childish dreams with me into this new year.