When I pronounce the word Future,

the first syllable already belongs to the past.

When I pronounce the word Silence,

I destroy it.

–Wisława Szymborska

Someone once told me that there are two kinds of stories in this world.

This:

a stranger came to town.

Or that:

I went on a journey.

But what story happens when you’re the stranger and your journey is back the way your family came?

And what kind of story starts when you know everything about it. Except where they began?

***

Once we built sandcastles, with our faces to the sea and our feet in the sand. I remember so much color. His silver hair and my brown legs, grey birds and white clouds and the blue blue water. And the way the saltwater chapped my lips, the way his bridge work glimmered in the California sun each time he smiled at me smiling, how the waves swallowed all sounds, even of their own crashing.

We packed the plastic molds–turrets, towers, walls–with a mortar he mixed with dry sand and sea water. The first time we needed more I walked towards the sea. No, my grandfather said as I reached for sand behind the wave’s lips, We don’t start with wet sand. We mix our own sand and water to build sandcastles.

The rye bread dough I’m mixing now has the same texture as that sand thirty two years ago: viscous and thick and pliable. It pulls at my hands as I work it, slurping moisture and sucking air. It feels heavy, dense–something between potter’s clay and thawing ice cream.

I’m not on a California beach but in a bakery after sunset in Warsaw, Poland. Pigeons are on the windowsill outside and someone in an upstairs apartment is braising cabbage with pork belly in paprika and apple cider vinegar. People I don’t know, people who work here, have gone home and left me with my flour and water and salt and sourdough and instructions on how to lock up when I’m done.

As I’m mixing the rye dough, I look through the front window and I see a stranger stop a stranger by touching his elbow. In a slow pantomime the man takes a cigarette from his lips and gives it to him, who uses it to light his own. The stranger bends, bowing almost, and cups his hand around the ember as if he’s telling the cigarette a secret.

I add more water to the dough and it squishes between the webbing of my fingers. I want it to feel like the sand I made with my grandfather that day. Rye is a fickle grain: it slurps, doesn’t absorb, water. Its quality of gluten is low and so cannot form a matrix; the key to rye bread is to gel the gluten by providing it with just the perfect balance of water and sourdough starter. It’s so unlike the wheat flour I’m used to.

Papierosy I say out loud. What a beautiful name for a cigarette.

***

I’m in Poland to teach two bread workshops. But really, I’m here to learn. I tell people to learn about where I come from. That’s not the truth though, cause in some way I’m too ashamed to tell the truth, to say that I’m really here to learn about myself. I want to learn about who I am by understanding where my grandfather was from. Because for some reason I’ve always thought that if I could make sense of his life, I could better understand my own. My thought was that if I came to Poland, I’d find clues about him which would help me with me.

I look down at my hands doing this work. This Polish rye dough sticks to my cuticles and knuckle hair and the scars where bread knives have cut my skin and where the steel hooks of electrical mixers have broken my bones. This dough is clingy, so sticky, and it’s difficult to read when it’s had enough water.

I was eight when he died and I don’t remember his hands. Just his silver hair and the smile like he chewed tinfoil, the Seiko watch from Chinatown, the gold chain with his astrological sign resting in a pasture of chest hair. And I remember how my grandmother kept him alive by telling me his stories. Like a sourdough starter, she kept him alive by leavening each new story she told me with a small portion of the old. And those memories, those stories, have the texture of this dough: moist, pliable. But unfinished between my hands.

So I add some more water.

***

My cousin died before my trip. A brain tumor. 60, 62, full of life. My mom and I went to see her before she went, drove through orange groves and dirt roads to her tract house by the sea.

Her bedroom smells like Clorox and Listerine. A humidifier sputters and her thin gray hair is strung across the pillow like a cobweb. The curtains are parted, so there’s a gap with a triangle of sunlight pouring through. Her boyfriend goes to the window, draws the curtains tighter. She is so small I could pick her up.

After he closes the curtains, he takes ice chips the shape of bread crumbs and bends in front of her. Then he circles her mouth clockwise, tracing the flushed and collapsed place where her lips used to be. The last warmth of blood in her lips and the blood in his fingertips melt the ice so she can drink its drops. Clockwise, clockwise, clockwise he rubs. Every now and then she gasps, trying to get more air. But her brain is nearly gone, it doesn’t need more air does it? Still she is telling herself the story of breath.

She was the cousin who loved me most. The one whose grace and cheer scared me. And she was the family’s secretary: she knew all the karma, all the plots, all the offstage drama. She knew all the things I was too afraid to ask my mom about my grandfather. And now I remember what I want to know as she lay dying.

“Wait until you go to Poland, Graison,” she’d always say. Her face lit up like a Christmas tree every time she did. “So much will make sense.”

This is goodbye. I tell her so. And I say, “Sandy, I’m going to Poland soon.”

I shake hands with her boyfriend, his fingertips are all wet.

From the car, between sobbing, I text my friend Monika.

I’ve come to Poland because of Monika Walecka. She is so many things: energetic, loving, fierce, insatiably curious, entrepreneurial, manic. Her bakery is a bee hive and she is the queen.

We’ve talked, for the past decade we’ve known each other, about fatigue. We’ve talked about spelt and spiral mixers and rye and employees. We’ve talked about poolish and biga and sourdough starters and the best kindling to start a wood fired oven (oak! Not the best–birch! Too moist). We talk about the things which bind bakers more than gluten.

But really what I’ve always wanted to talk to her about is Poland.

“When can I come?” I’ve asked for ten years.

“You can come home anytime,” she’s always said.

I text her in the car after leaving my cousin’s house. “Monika, I need to come to Poland.”

***

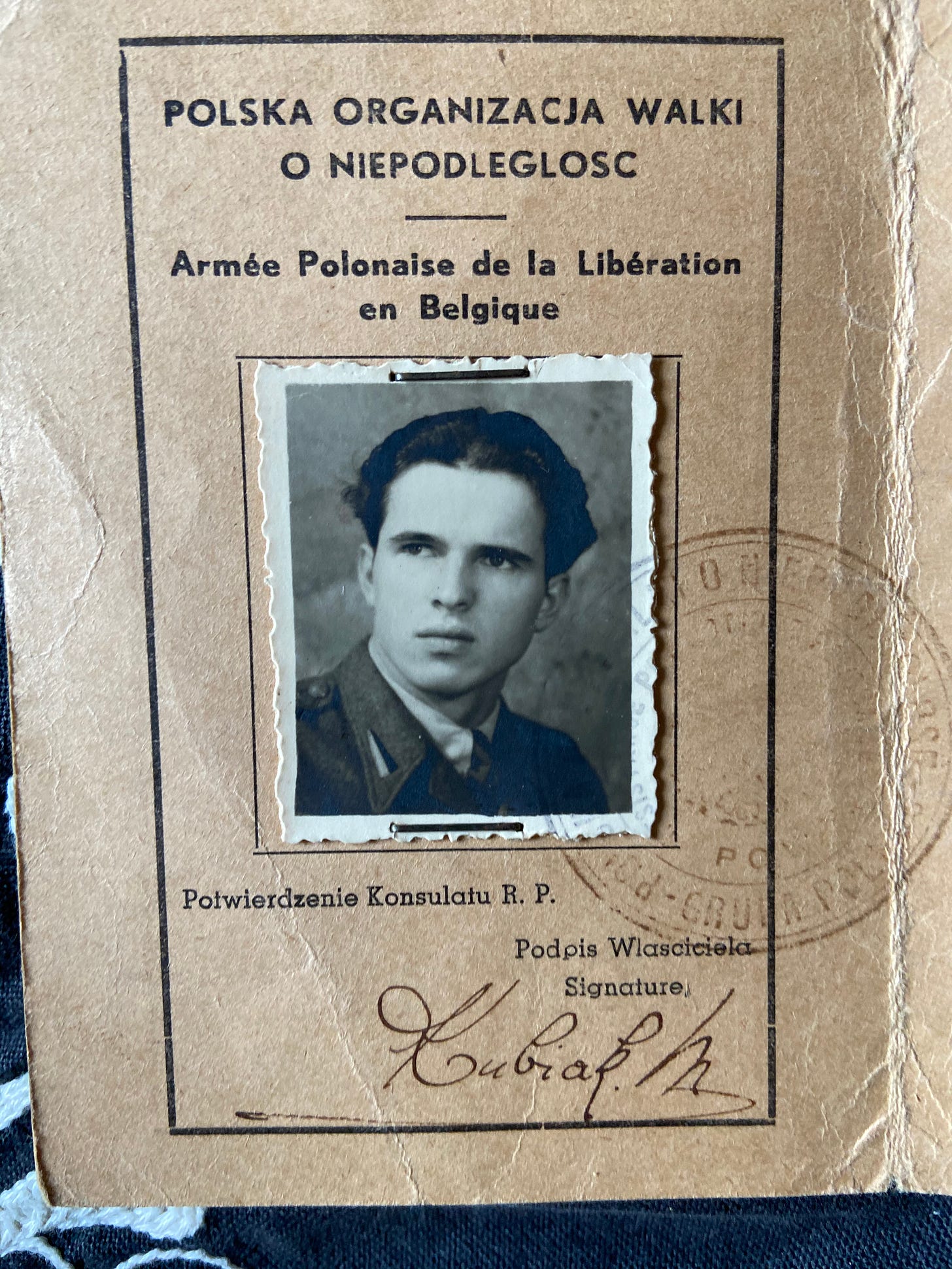

My grandfather, Mieczyslaw Józef Kubiak, left Poland during the Great Depression. His parents took him and his younger siblings to Western Europe to work on a coal seam. He went to school until the fifth, maybe sixth, grade. But there aren’t wages in school–so he got an education while working in the mine, while working in the sugar beet fields.

His mother Eva took in boarders, laundry, and tailoring. She raised rabbits for meat and pelts, and she sewed. Trousers and napkins, dresses and curtains. Long dresses, long curtains; she became known for her hemming. And for the sourness of her Eastern European rye bread in that land of wheat.

His father Józef spent all day beneath the ground. Chipping, crushing, breaking earth which groaned each time his metal pick struck it. Then, when he went aboveground, he did the same to everyone in the house–he broke and crushed them with his belt and with his fists. Leaving bruises the color of borscht, welts the color of spring roses.

My great grandparents. Two people, like me, who were very good with their hands.

“Bread is a way of telling your story. It’s how you tell the world who you are, where you come from, where you are going. After all, us bakers only have three ingredients to tell our story–flour, water, and salt. So what do you want your ingredients to say about you?”

I tell this to all my students, who’ve numbered about 2,000 by now. I tell them this is why I use freshly milled flour to make my bread: because unlike white flour, it has an identity. Fresh flour has a farmer, it has a soil, it has a flavor, it has a name. Freshly milled flour has its own story.

The flours in Poland are beautiful. Wheats as dark as my hair before the stress, einkorn creamy and blond as Dutch cheese, rye the same blue-grey as oysters, black emmer the color of fresh cracked pepper, purple wheats the color of amethyst. Their textures are gorgeous, too: sand, polenta, ash, bread crumbs.

During my workshop in Poland I ask everything I can about these varieties–their names and the names of their farmers, their histories. But too often the students say, We can’t translate it, it won’t make sense, or I don’t know. Often the answers my grandmother gives when I pry too deep.

“So in this class, I want us to tell a story about Poland through its flours. I want us to tell a story about where we are–about where we come from–with flour and with bread.” I’m telling this to my students right before we start mixing the doughs.

No, I’m telling this to myself.

***

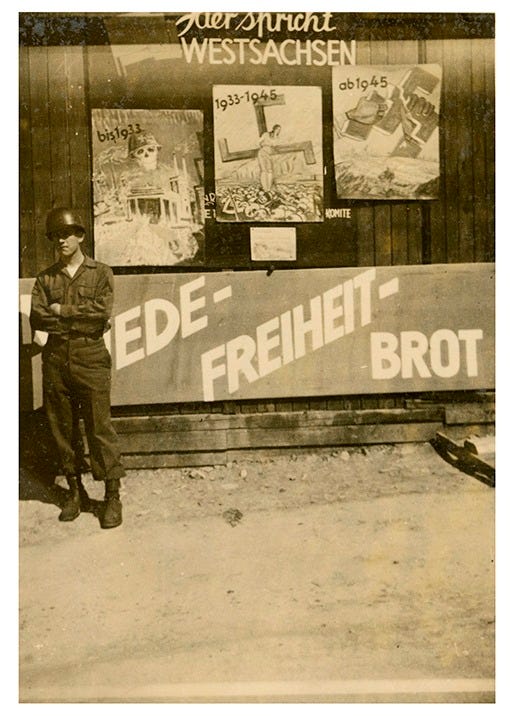

When the Nazis arrived in the little village where my grandfather lived, the men departed. Especially immigrants like our family, they ran the quickest–to the forest, to Dunkirk, to Spain. Machinists, priests, laborers, bakers, miners–when the Germans came they all took the same job: partisan. Immigrants with nothing–no mortgages, no automobiles, no educations–risked everything. What were they fighting to protect–their bicycles, the job at the mine, a few yard chickens?

All the men of my family ran. But before my grandfather turned sixteen, his father and brother were arrested by the SS for their new jobs: running guns between the French Resistance and the Polish Resistance in France. They spent the rest of the war as slave laborers in Buchenwald, making rockets for SS Sturmbannführer Wernher Von Braun, the future deputy director of NASA.

The evening they were arrested, my grandfather leapt out of a two story window. No time to move aside the curtains. No time to grab the rye bread his mother just baked.

He hid in the woods for days. And when he came out, at the age of 16, he fought against the men who came for him.

But like so many of these soldiers, the ones who won the war, the men of my family had an awful time living with the peace. Grandfather came back from the woods, yes. But I’ve always wondered if he, or any of them, ever came back from The War.

I don’t know but I think it wasn’t what they saw or had to do which tore them up. It was the not talking about what they saw or had to do which hurt the most: the story didn’t hurt as much as not telling the story. The way it just fermented, just bubbled and gassed and proofed, like an unattended sourdough starter. And because no one opened its lid, it shattered the jar which held it. So it oozed–with its acidity, with its warmth, with its mess–all over the kitchen and everyone around.

I’m sleeping in Monika’s old flat. The whole apartment is the size of an American bedroom. The tapwater tastes like the headache it gives me: metallic, bitter, heavy. Across the way neighbors hang laundry to dry while drinking liters of Fanta and listening to Abba into the night. Me and my jetlag sit on the balcony and watch Warsaw sleep long after the music stops.

The first morning there is a blinding light which rushes me awake. At first I thought there was a problem–an explosion, an electrical issue. It takes me a minute to realize it’s daylight.

The bedroom windows have no curtains and I can’t sleep with this brightness. In June in Warsaw the sun comes up right after 4am. And throughout the first week I try everything to keep it out: nailing old towels to the window sill, tucking sheets into the gaps, wrapping shirts around my eyes until I look like a hostage. But nothing works, the sun stabs my eyes and I cannot sleep. I need curtains.

One night I go to a mall. I buy 3 lbs of smoked sausage, ½ lbs of smoked herring, a jar of pickled beets, six bialys, and some seltzer. And I buy curtains from the drugstore.

That first night with the curtains, when I know it will actually be dark, I fall asleep deeply. But my phone buzzes about 4am. The bakery is texting me.

“Graison hi sorry your sourdough exploded all over do you know what to do? is this your fault?”

***

In 1952 my grandparents sold their curtains, sofa, armoire, and mattress. With that money in their pocket, they took a bus to a large clinic with stone pillars and revolving doors. Inside the building, pressed into its soapstone walls, were bullet holes like cavities in a soft mouth. There they waited a few hours with strangers–men and women with little black tattoos on their wrists–to get their x-rays taken.

A month later, with nothing but overcoats, two trunks, and two new silver filings each they arrived on Ellis Island. My grandfather gently pushed two clean, unblemished manilla folders across a clean, polished mahogany desk towards an Immigration clerk in a powder blue uniform. In one folder were those x-rays, proof that they didn’t have tuberculosis. And the paperwork in the other was the address and paystub of a cousin in Massachusetts with a name no Anglo clerk could pronounce. All this paper was proof to America that they weren’t sick or helpless.

Fifty five years later, I went to Ellis Island with my grandmother.

It was here, she said, I think it was here. I was drinking out of a water fountain, wiping my lips on my sleeve, just as she began this story. The sandwich machine, she says. Of everything about our trip it was the strangest thing: I don’t remember much but I remember that they were selling sandwiches inside a machine!

Yes Grandmother, that is strange. No, no, not really. It was the bread, the bread that was strange. It was so white! I’d never seen anything like it before.

She could have told me any story about the Old World, she could have told me any broken promises of this New one. But she told me about bread. I wasn’t even a baker then, I was still just me.

Everywhere I go in Poland smells like my grandparent’s apartment. Caraway, rose hips, foamy pilsner, melting butter, stewing apples, briny cucumbers. Whole blocks smell like Melitta coffee and un-pasteurized milk and old newspapers. I step into rooms and can tell that the dishes have been put away bone dry, that every scrap of food was saved, that a candle will be burned to its last knuckle.

In Poland I’m reminded of the smells of old people: of just-licked postage stamps, of glass jars holding spare coins, of bottles that are waiting for their deposit to be returned, of woodsoap and a leather chair that’s been sat in too long. It feels like everything here reminds me of my grandparents, especially of their dignity which never wanted poverty again.

I’ve only been here for three weeks, yet it feels like home. Many people look at me and begin speaking Polish and are confused when I don’t respond. And the food tastes like how I feel–calm, nourished, home. The food tastes like the parts of me which went away when the people who put them there died or left. But when I eat, I get them back.

So I stuff myself. I waltz between cheap milkbars and butcher shops, between family restaurants and street stalls. I eat borscht with the texture of velvet, potato pancakes fried in fresh rapeseed oil and topped with cream the texture of a fallen cloud. I drink fruit compot and malty kvass. I buy melons with the color of flesh, herring smoked and pickled and pureed, eggs deviled by god. And then there’s the bread.

But when my belly’s full I’m ashamed. Because I remember the stories of Hunger–the stories of ration cards, of the camps, of failed harvests. I remember hearing stories about the choices between betrayal and food, the choices between feeding a young child or an old man. The stories of those who didn’t get out from behind the Curtain. And what people didn’t have time to bring when they ran into the woods to fight.

Still I eat. Because flavor brings me back into his arms and smells bring me back to my grandparent’s apartment. And I’m reminded of how their rituals helped me when I sought refuge from what was happening in my home. My grandparent’s food wasn’t just comfort; it was protection. It gave me what I needed when I didn’t have it.

What are grandparents? Just more authentic versions of our parents. And what do grandparents hide, what do they sacrifice, in order to protect us? Behind the smiles, behind the pride, how much did it hurt grandfather? What did you look at and could not un-see? Why do I feel like I know what you have done?

***

In between teaching, I walk Warsaw. I get a haircut from an Ukrainian barber who has a python named Putin. I buy foraged mushrooms and wild strawberries from a woman with glaucoma eyes muddled like a martini. I sit on park benches and feed ducks stale bread, I wander alone through empty playgrounds. I buy a newspaper, nicotine pouches, fresh lard for the warm rye bread pressed between my torso and bicep. I take the long way home so that I can hear laughter from schools letting out. And then I put my keys inside the door to a building where no one knows my name or his. I wonder.

Did he ever walk these streets? Did he ever feed these ducks, taste the brittle seeds of a wild strawberry, hold a woman’s hand in the same places I walk now? Did he ever look into these same windows, wondering how all these people sleep?

I go to a museum. A sign says:

Population of Warsaw 1939: 1,300,000 (more than Rome and Madrid)

Population of Warsaw 1943: 600,000

Population of Warsaw, January 1945: 1,200

90% of Warsaw was destroyed by the Nazis between September 1939 and January 1945.

My grandfather and I each knew a different Poland.

If our paths ever crossed in this city, it wouldn’t recognize either of us.

“I know little, as you do, surely:

Under my town the river flows,

Bronze statue stands over it

And houses on the right and left

In which people with faces like ours

Lie under the sheets, eyes squinted

Tired as clouds

Gazing into their dreams as if into the mirror.”

—Tadeusz Gajcy (Polish Poet, Playwright, and Soldier)

This is how I remember him:

With an accent thick as goulash. And that he never wore t-shirts just button downs, that he had a different glass for each beer, a saucer for each cup, a ring for every finger. I remember his bridgework and filings (six by now), that gold Seiko watch from Chinatown, muscles warm as proofing dough, a smile that could light a candle.

Yet now he’s too weak to even lift a match. And his breath smells like sick people’s breath, like cabbage stewed in too much vinegar. Before this he had an appetite like a farm animal. Now he gets his meals through straws.

It’s the Christmas before he dies and he’s taking chemo. But really, the chemo is taking him.

I climb onto his hospital bed and draw the fabric of his Lacoste polo shirt between my thumb and finger. I love the texture of its weave, its weight and soft prick, it reminds me of my baby sister’s new teeth. I want to run my fingers through his silver hair, usually oily and firm from the tube of VO5 he keeps on his dresser next to his horn comb and bank roll. But most of his hair is gone. So instead I feel the stiff skin on the back of his elbow as I ask him to lift me up. He can’t, but he puts his hands on me to touch me and to feel me and to say a different kind of goodbye. He tussles my hair, tries to make an impression of Daffy Duck, asks me if I want to watch Rocky and Bullwinkle. My mom, between tears, says it’s time to go.

I realize that the way he was touching me then is the same way I touch bread now. Each day I feel bread I hope it remembers me, I hope that it still trusts me. Because my hands always know what dough needs, how it needs to be shaped and touched and formed. But if I tussled the rye bread dough the same way my grandfather tussled my hair, it would collapse.

He taught me to ride a bike. He taught me to kick a soccer ball. And I got his thick hair and dark eyes, I got his temper, and his metabolism. He taught me about those sandcastles. And then that was all the time that God gave him.

***

Rye bread is not shaped. Instead, it’s just formed. This is because during its rising–polysaccharides called pentosans–swell the starch in the flour. So instead of forming a complex gluten network like wheat flour, rye bread is slowly swelled. And the baker has to do nothing to shape rye bread. They only have to keep a very careful eye on the fermentation, to ensure it does not go over, to be sure just to catch it in time and load it into the oven.

For the past sixteen years, I’ve shaped tens, hundreds of thousands of loaves with wheat flour. I’ve forced them into the weights and shapes I want–baguettes, ciabatta, couronne, fougasse, boules. I’ve used pressure, torque, and power to contort and press and punch down the rising wheat dough. I’ve used knuckles and wrists and tendons and muscle. I’ve done this over and over and over again. I’ve never just let bread dough be. I’ve always touched it, always shaped it, always formed it into what I wanted it to look like. And it has always let me do what I want.

The bread of my grandfather’s Poland is rye. A baker just mixes it, forms it into a pan because it cannot stand alone, and the pentosans take care of the rest. You just have to gently, with wet fingers, pick up the dough and move it into a pan. From there, rye bread forms itself.

Someone pops a beer can, baguettes coming out of the oven sing with heat, Monika laughs like a sailor. It’s nearly 90°. This is the last day of class and everyone is busy.

In between baking and sweeping the floor, I chat with a student. Milosz is a farmer in the South. He bought a Russian stone mill (bad timing! he laughs) a year ago. It’s taken us ten minutes to understand three things: we both like to fish, we both like to hunt, and he’s invited me to his farm to do both. I have a million things to ask him about wheat and Poland and his journey. But I don’t know how to express myself, I don’t speak the language of this stranger.

My fingers are wet and covered in dough. But I manage to pull up a photo of my grandfather. Kubiak! I point to him, then I stick a doughy finger onto my chest. Milosz cocks his head like a puppy. Kubiak! Kubiak! I say my grandfather’s name again. Then I pull up his birth certificate, his ration card, images of him with his battalion. I point to the name of the village where he was born, written in long cursive.

When we grow tired of miming and gesticulating, we grab someone to translate. Anna comes over and I ask her to ask Milosz if he knows the village where my grandfather was born. She explains, and he tries to pull it up on Maps. It won’t load–his reception is bad. So I pull up Maps on my phone and type in the village name. Little veins of streams, tiny tinsels of county roads, green shaded woods, rivers like roots slowly form a network around its location. I ask Anna Can I go there? Is it easy? Milosz said he’d take me. But its location isn’t very clear because I also don’t have good reception–none of us can tell exactly where it is.

So there we are, me pinching the map on my phone, zooming out, zooming out. My wet fingers sliding across the screen and Maps still won’t load, the village won’t clear. I’m zooming out, I’m zooming out, trying to show someone else where my grandfather was from, trying to get myself to understand where I’m from.

And then I’ve zoomed out so far we’re starting almost at a map of the entire un-downloadable world. And yet I’m still trying to see my grandfather’s village, zooming out and pinching it like I’m trying to pick it up. As if once the image clears, I’ll shape it. As if doing what got me here will bring me any closer to why he left.

What a beautiful way to honor your family, especially your cousin and your grandfather. We carry so many histories with us... from our families, their countries, our own experiences.

Thank you for sharing, always looking forward to reading more

Really great read - 🙏