I wrote this piece many years ago, right after I turned 27. I became tired of it being rejected for publication; so I gave it a shave and put some new clothes on it. Lemme know what you think. Thank you

My body is my compass, and it does not lie.

Terry Tempest Williams

IN THE DARKNESS of our room, I draw my soft flesh against her hard granite skin. Her stones are warm, the temperature of blood. And I know her body well when she is undressed, splayed and naked like she is now upon our bed of pallets and 2x4s. I put my lips to the warmth of this damsel and close my eyes.

We are alone and I like her best like this: 3am, the smell of the turkish coffee and baking bread and burnt butter and not even a siren or birdsong or a trumpet is whimpering in this Louisiana night. She lies still, but not me.

I traffic my fingers across her bosom, twist her corkscrew auger, frottage my thumb through her furrows and my cheek across her feather edge. I pinch her smooth waist, trace her subtle chamfer, stroke her heavy breast with my sweaty palm. I lift her shroud with my pinky, caress our bed stone, grope its brace.

I peak beneath her skirt. I see five taut black pulleys. Bearings in tight corsets of steel. A metal chain coated with flour and oil drooping like wasps nests. Iron shafts, steel nuts, rigid bolts, firm rods. A glinting, wet crankshaft. Grease points, like hard nipples, sheened with lobes of lubricant.

I brush my bangs away from my eyes and take off my glasses, blinking slowly in the darkness. I pack up our toys. My creeper, my chisel, and damp rags and aluminum ladder and ball pein hammer and torn gloves and carpenter’s pencil. Her shank, her slings, her cinched belts and grease gun and worn straps.

I take off my particulate mask and turn off the air compressor. It sighs softly as it bleeds. I graze my hands one final time across her tremendous body of warm granite, turn off the lights, and leave.

I’VE BEEN BAKING bread for years. And the fatigue of my 16 hour days doesn’t stop when I undress.

A stubborn pain winks like a lighthouse somewhere inside my skull and a thick pith of flour coats my lungs. I’ve had the same cough since Christmas and my eyes are as red as gazpacho. My shirts are stained, my teeth are stained, I never have more than a quarter tank of gas, and I’m afraid that bulge in my abdomen may be a hernia. My friends are tired of me being a ghost, my family wonders why I work so hard, the neighbors look at me with horror each time I have a coughing fit before lighting my cigarette.

My life is leavened by solitude. I work when others sleep. Sleep when others work. In the stale and soggy hours of my waking life, in my little atelier of alchemy, I trespass between sunset and sunrise like a werewolf, shuffling underneath the moon between the bakery and my apartment which is smaller than the bakery.

I lift too-heavy bags of flour, I burn my wrists and fingers and forearms on loaf pans and sheet trays, I cut myself on blades, I slip on wet floors. I numb my body so I don’t have to think about my mind.

SOURDOUGH STARTER IS a combination of equal parts flour, water, and already fermented sourdough. Bakers call this their Mother. The sourdough starter is the wheel around which a bakery spins: if a baker doesn’t feed the Mother, tomorrow’s loaves will not rise.

When I shave, when I change my underwear, when I pay my bills is dictated by the rhythms and the mysteries of my sourdough starter. I am the only custodian of its bacteria–I watch them grow, I feed them when they’re hungry, I’m there for everything they need. No matter if it’s moonlight, no matter if it’s daylight, I have to find enough light for our choreography.

It’s 11pm. I stir one tablespoon of cane sugar into my coffee. The brown granules melt into a small whirlpool, their texture disappearing inside the liquid’s dark warmth. I bring the ceramic cup to my lips, smell the sweetness before it evaporates into bitterness. It warms my tongue as I swallow.

One tablespoon of a baker’s Mother contains more microorganisms than there are people living on this planet.

Today I turned 27 and realize I didn’t look anyone in the eye.

AT HOME AFTER work I watch YouTube videos of ancient castles. I buy a roasted chicken from WalMart, a six pack of Yuengling black & tan, take home a torn and burned loaf with a jar of salted butter and settle into citadels, abbeys, fortresses. Walled, impregnable, hermetic, beautiful, made of granite. Mostly, I love the moats.

The presenter reads the grain of the stones used to build the structures. Knows by their color and texture and size where they come from. Who cut them, which abbot paid for them, which weapons were used to pull them down, what year after Christ this all happened. I tear into the breast, the thigh, wipe the schmaltz off my lips and fingers with the bread. All the while this man explains the past as if he owns it.

On my coffee table is a bowl of wheat. It’s the color of my skin after a sunburn. By now, I can take a palmful of wheat and read it. I will touch it, smell it, taste it, bite it. And I will know by its starch, by the thickness or thinness of the bran, by its toothiness, if it was irrigated, if it rained before the harvest, if the variety is what the farmer says it is. And while chewing these kernels, as they mix with the saliva and spit in my mouth, I get an idea of what kind of loaf they will make.

Is it possible to know more about what we do than who we are?

A woman comes on the screen. An archaeologist: argyle cardigan, chestnut bangs, a PhD, lips the color of sherbert, smarter than the man. She doesn’t touch the stones, doesn’t need to to make her point.

I haven’t kissed a woman in two years. The last relationship got overripe, like a sourdough starter mixed too warm and left out unattended: bubbly, gaseous, unusable. Too sour.

My eyelids grow heavy, the video changes itself, my mind wanders…castles, my birthday, moats, YouTube algorithms, beer bottles, chicken bones, billions of microorganisms in one tablespoon of sourdough culture. So why am I so lonely?

HUMANS HAVE ALWAYS crushed grain against hard rock to make flour. It was the Greeks, taught by the Egyptians, who perfected what we know today as stone milling.

A flour mill is simple. Two massive stones face each other. The bottom one, the bedstone, rests on a frame. It never moves. On top of it is the nether stone, the upperstone–the runnerstone–which spins freely against the bedstone. On top of this is a hopper, which holds the grain. As they begin to spin, the grain is fed into the stone’s eye by an augur and as the wheat berries travel across the opposing faces of the stones they get chipped, crushed, then pulverized before being pushed off the sides. This is how flour is made.

After baking for six years, I began milling my own flour.

The flour I was buying was dead: white, tasteless, empty. It was too much like I felt. The loaves it made were too plain, too predictable. They lacked honesty.

I wanted to work with flour that was alive. Warm, colorful, healthy. Fresh and moist and clumpy. I didn’t know where to get this kind of flour. So I decided to buy a 2500 lbs stone mill and make it myself. Except for the use of electricity, I began to mill my flour with the same materials, in the same exact way, which those Egyptians and Greeks did so long ago.

But If only I knew how exhausting stone milling would be. How dangerous and tiring and dirty. I’m now covered in even more flour–my shoes are caked, ankles matted with sweat and flour, arm hair dusted white as if I took a shower in talcum. When I sit down a plume lifts from my pants, when I lie down the pillows of my bed sigh into a cloud of its dust. Flour is in my septum, in the folds of my ear, under my nails, stuck to my harelip. I taste it in my mouth even after brushing my teeth.

I asked the engineer who built my mill how long the stones will last. The miller will wear out before the stones ever do, he tells me.

BREAD BAKING AND flour milling are about doing the same thing, in the exact same way, every single day. And the measure of success in both crafts is if nothing today comes out different than yesterday. So each day I have to make the same perfect flour, the same perfect loaves, unrecognizable from yesterday’s. I’m doing my job well if I can duplicate the past without anyone noticing. I’m enchanted by this power: I tell the world a story about bread and it believes me.

After years of this work of milling and baking, the flour I mill and the bread I bake has become a moat I’ve dug between the world and me. Grain by grain, sunlight by moonlight, loaf by loaf, the waters deepen. Sometimes I can’t recognize the truth in my stories anymore.

How old are the stones on my mill, I ask the engineer.

About 60 million years old, he says.

I just turned 27.

Already this life is ancient.

*****

IN A LAND before time, lava erupted. And when its tantrum was over, it cooled back into the earth, sleeping for millions of years in a slow, anaerobic lullaby.

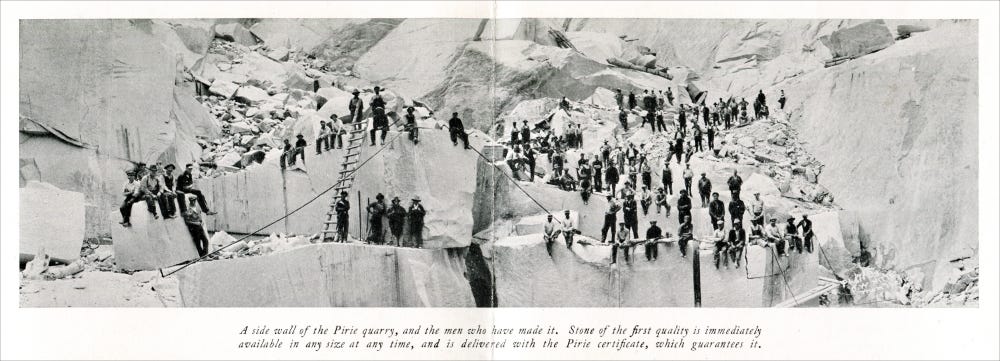

60 millions years later, quarrymen came to shake this cradle awake.

These men left the Old World for new work: Italian anarchists, Canuck Fabians, Irish Fenians, Polish drunks. When they arrived in America they cleaved, they hammered, they chipped, and they blasted the granite apart at the country’s most famous quarry: Rock of Ages in Barre, Vermont.

The quarrymen’s honest labor was prized. Emma Goldman, Big Bill Haywood, and Eugene Debs came frequently to organize and inspire and advocate for them. Still, many died from this work–from crushing, from coughing, from fatigue. They were hard men. And yet they heaved. It was hard rock. And yet they hewed.

This granite torn from the earth’s past was used to build America’s future. Half of the nation’s state capitols were made with this gray granite. So were the grand columns for JP Morgan’s banks and Carnegie’s libraries and Rockefeller’s stately homes. And this granite was used to make tombstones and fireplaces and paving stones and fountains and boulevard curbs and monuments around the country. But mostly, it was used to make millstones.

My granite mill stones are huge. 1000 pounds each, 8 inches thick, 48 inches in diameter, cloud gray with black peppercorn freckles. Both stones are monolithic pieces of gray Neolithic granite, composed of quartz, biotite, feldspar, and mica. It is incredibly hard, perfect for flour milling. I cannot lift them, I cannot move them. I can only touch them. But even when I open my arms, as if to hug them, I cannot fully embrace them.

The granite stones I use to mill my flour come from the Rock of Ages quarry in Barre, Vermont.

Quarrymen in a Barre, VT quary, photo credit: Quarriesandbeyond.org

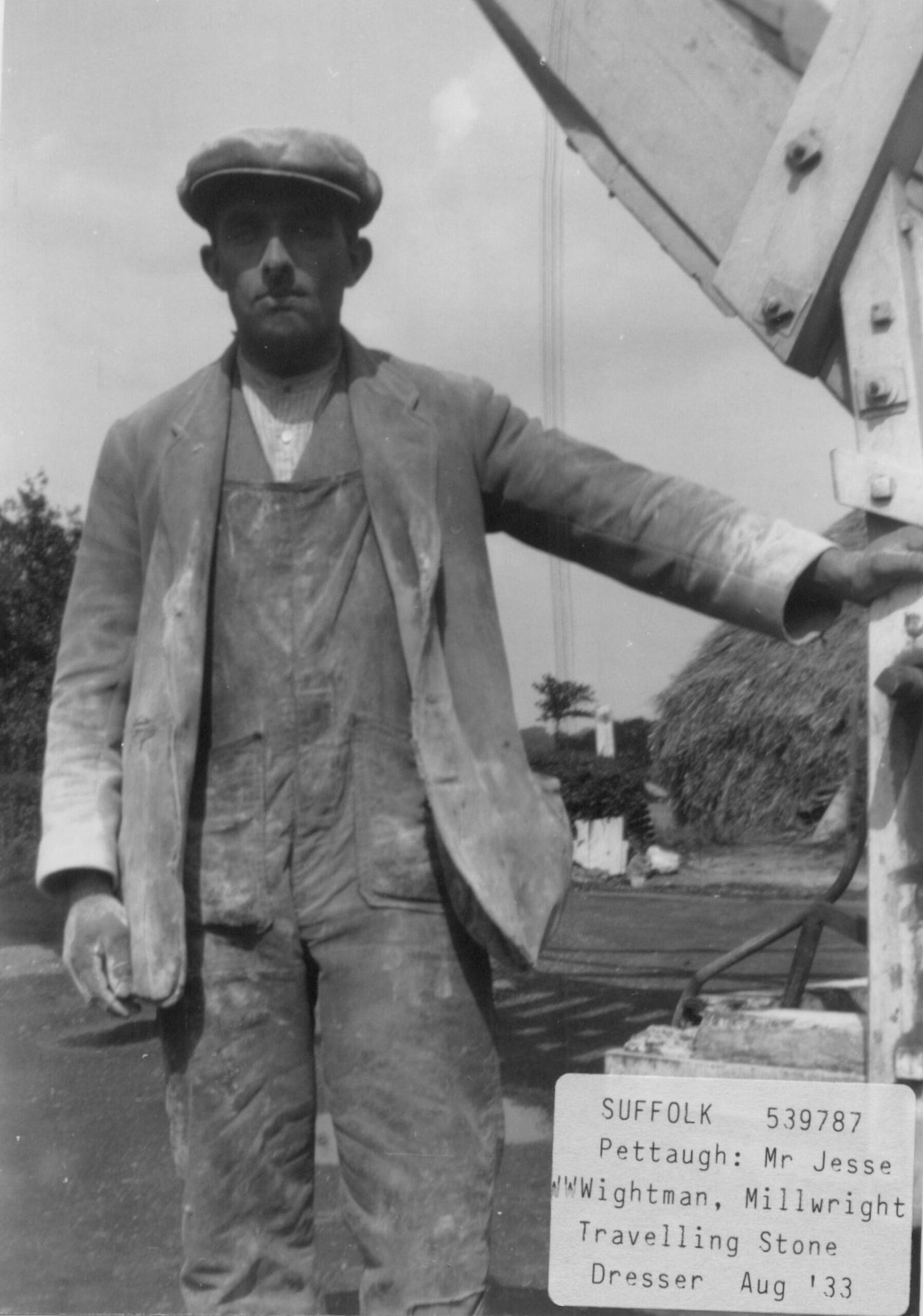

MEN WHO MAKE and fix flour mills are called millwrights. They are highly skilled craftsmen. Until very recently, they were itinerant because due to the weight of millstones, work was never brought to millwrights. They brought themselves to their work.

In elaborate seasons of migration they went round their circuit with nothing but what they could carry. Men with slate wedges, with star drills. Men with mash hammers, with bush chisels and tape measures and white chalk and hemp rope. Walking across the country from county to parish, from parish to territory, from territory to outpost, they went where millstones needed maintenance.

The millwright did what needed being done, fixed what needed fixing, on the millstones of his customers. He slept in their dirty barns, in his raw denim and stained corduroy. He smoked what they smoked, ate what they gave him: goose eggs and goat milk, salt pork and johnny cakes, corn husks and sorghum molasses. He smelled the poverty of their lives: green woodsmoke, candle wax, damp leather, fresh manure.

Jesse Miller, photo credit: Millersarchive.org

EACH TIME A millwright arrived to a familiar strange place, the first thing he did was open the community’s stones. Then, moving amongst them cautiously, like a new lover before the first kiss, he let his fingers and hands read the granite like braille.

A mill stone is dressed before assembly. To dress a mill, the millwright chooses a pattern, chalks it upon the nude faces of the stones, and begins. The dug grooves and the subtle valleys he cuts across the face of the granite, with tapered channels and thin rills he digs are called furrows. These act as streets and alleys for the wheat berry to travel as it spins from the eye of the mill outwards. The rest of the stone’s face is left uncut and these are called the lands.

Unsharp stones will mill flour which is coarse, uneven, clumpy. Because the longer a mill mills, the more the stone is worn down by the grinding. Before dressing, the face of a dull millstone will have the texture of melting ice: smooth, slippery. After dressing, the face of a sharp millstone will have the texture of a dog’s tongue: rough, prickly. To sharpen the stones, the millwright will use his chisels and hammers and drills to shave away pieces of granite no bigger than an eyelash. Methodically, intimately roughing up the face of the stones he works alone inside a reef of dust, granite, and flour.

And the narrowest hinge in my hand puts to scorn all machinery.

Walt Whitman

MILLWRIGHTS WORKED IN heat, in dark, in damp. They walked like cats across creaky barn beams, fitting their bodies into spaces no bigger than a coffin to work the stones. Each gesture with a metal tool was pregnant with risk, each stroke of a match for light or for a lungful of tobacco could be their last: few things are more combustible than accumulated flour. Worse, the suspended stones could drop at any instant: the millwright would be dead before he even felt their weight.

As the millwright’s dressed the stones, the mill owners gave them the moonshine and the gossip: bad harvests, new religion, worse taxes. But before the owners opened their mouths, the millwright had read the stones. He knew these stories were false: he knew what the stones had seen by how worn they were, by how much flour was pasted onto their faces. He knew where the stones rubbed, how they faced off, if a leather harness was chaffed or a steel bearing was thirsty for oil. And he could tell who broke something by how badly they fixed it.

Once splayed apart the millwright saw the footprints of time written by the flour ground on the stones. Like a palm reader, he translated the marks. Soft earth, chalk, dried dung, pebbles, bones–he knew which fillers the miller used to blend with the grain, to bulk out his flour, to stretch out his profits. These secretes–milled into the community’s flour and leavened into its bread–cut the stones in the wrong ways, damaged them. People tell stories. But wheat and granite cannot lie.

Cutting and chipping, dressing and undressing, his nose to the grindstone all day long. The millwright brushes away the dust, feels the newly sharp stones beneath his fingertips. He pauses to feel what he’s feeling. His hands know more than his mind.

So much is known by a touch, so much is seen with a gesture. So much can be hidden by words.

Millwright, working an overshot water mill, photo credit: Millerarchive.org

NIGHT FALLS. Work ends. The millwright is shown to his pallet on the floor. He is given a lantern, a blanket, a jar of cold coffee. His joints creak, his back moans, his knees are frozen from work. His bones try unfolding, stiff as dry rubber, in his patch of wet straw. He goes to bed with his work: dust spores and flour clumps and granite flakes.

All day his body has touched hard granite: now he wants something soft. Constantly moving, he has to find pleasure when he can. So he dreams someone will join tonight’s loneliness. Maybe in this hayloft a farm boy or the milk maid he winked at or the miller’s wife will wander cautiously, asking if he wants another jar. If not, perhaps he’ll wander to the stable below.

THE MILLWRIGHT WAS lonesome, not quite a stranger, but ineligible for membership in the community whose stones he dressed. Because no one trusted the millwright. How can a man who wanders between granite stones keep a home, keep a church, keep a wife? So against him mouths were cupped and lips brought to ears. Rumors were levied, womenfolk and family heirlooms concealed when he came to town. This bronchial vagabond, draped in flour and dust as if a living ghost, caused alarm. He spent more time with granite than people, he was a man who left as soon as he came, he was a man whose only story was his work.

Despite this mistrust, everyone needed his craft and the alchemy of his hands. The people had to have their flour, the people had to have their bread. So the people had to have a millwright.

But always familiar to him was the truth in the granite: such durability, such loyalty, no matter where he went. So he followed the constellation of millstones, spread across the country like terrestrial stars. No matter where he went to dress and undress stones, he could trust the stroke of his chisel, the white in his chalk, the patterns on the millstones he opened. Because of these truths, he had little use for settled men’s fictions.

His journey starts again. He packs his tools, he folds his money, combs his hair, shakes a hand or two. His feet walk, his body moves, towards the next set of stones needing dressing. But somehow, in doing the same thing everyday, his life stays put.

How do you tell a story that never changes?

Mill Diagram, image credit: Theodore R. Hazen on Angelfire.com

MILLWRIGHTS GAVE THEIR work the anatomy of the women they yearned to feel. Breast, skirt, eye, damsel, bosom, bedstone, shroud. These are the parts of a millstone, named by the loneliness of the men who undressed and dressed the granite everyday: they couldn’t have a wife, so they made granite their bride.

Each night after work they couldn’t settle into sheets which weren’t their own, they couldn’t go home to homes they didn’t have, they couldn’t stay with women who weren’t theirs. And because they couldn’t have what they wanted, they did the next best thing: they made up a story. In telling it they were able to say the words they yearned to feel.

Breast, skirt, eye, damsel, bosom, bedstone, shroud.

Dressing stones is tedious work, it takes concentration and care. The millwright mounts the stones to get into position. He bends his knees, or gets down on them. He squints his eyes, squirts his oil. His body and limbs have to be pliable, vulnerable to whichever position the stones need him to take. Then he begins his work.

But sometimes there were accidents, or revenge. A pin suspending the stones could come ajar, an animal could startle, a structural beam could collapse. And when the stones fell, if the millwright were lucky, he could get most of himself out of the way. Failing that, a limb, a finger, or a hand would be caught between the crashing granite. And when this happened, and if he lived, the millwright said he got a granite kiss.

This is beautifully written. I look forward to many more writings!

This is gorgeous. I lost count of the phrases that knocked the wind out of me. I've been mulling over milling lately, so this couldn't have arrived at a better time. Beautiful work.